Tambopata – A tropical paradise in the shadow of gold | Part 4

Films for conservation

Films for conservation | by George Olah on 01 November 2020

It was dawn in the southeastern Peruvian Amazon. After an early start, we were heading to a clay lick with nature filmmaker Bertie Gregory in a motorised canoe. The air was humid and still very cold, especially in the headwind of our boat. But we had to hurry as the rainforest was already awakening. We unloaded the film gear to a dry patch of rocky riverbed, a few hundred yards from the clay lick, and launched the drone. The macaws also woke up early and were already on their way to fetch their “breakfast of clay”. We filmed them for several months, escorted them with a drone from a safe distance, and inserted a remote-controlled camera inside a nest. A few months later in November 2019, we gathered with the film crew again in somewhat drier conditions, this time in a pub in Bristol in the UK. The occasion: the premiere screening of the South America episode of BBC’s new series, Seven Worlds One Planet. The macaw scenes of Tambopata appeared on the big screen with David Attenborough narrating the scientific findings of the macaw research team. The premiere was watched by more than 8 million nature-loving people that night in the UK alone.

This was not the first time we have worked with the Natural History Unit of the BBC, which is well known for their spectacular landmark wildlife documentary series. A few years ago, my cinematographer colleague Balázs Tisza and I contributed to the episode about the Amazon in their series Earth’s Great Rivers, which we also filmed in Tambopata. Indirectly, films can have great power in nature conservation by providing important background information, raising awareness about conservation issues, and inspiring viewers to make responsible decisions in their everyday lives to protect the natural environment. The huge viewership of Attenborough’s nature documentary films is undeniable, and they have inspired many people to learn more about nature, or like me even to choose biology for their profession.

More recently, blue-chip nature documentaries have captivated viewers with their amazing visual worlds and the use of state-of-the-art cinematic techniques. An increasing number also report conservation problems and the projects that seek solutions, though most still try to present nature in its unsullied, beautiful state. As a conservation biologist, I co-founded the nonprofit organisation Wildlife Messengers with my colleagues, primatologist Cintia Garai and photographer Robert Carrubba. Our primarily mission is to make educational films and videos based on strong scientific background, specifically for conservation purposes. On one hand, we have a friendly network with other filmmakers and a growing experience in wildlife documentary filmmaking. On the other hand, our research background helps in selecting important conservation topics and locations, and certain sites – like the Candamo Basin in Peru – are almost exclusively only accessible with biological research permits.

The Candamo Basin

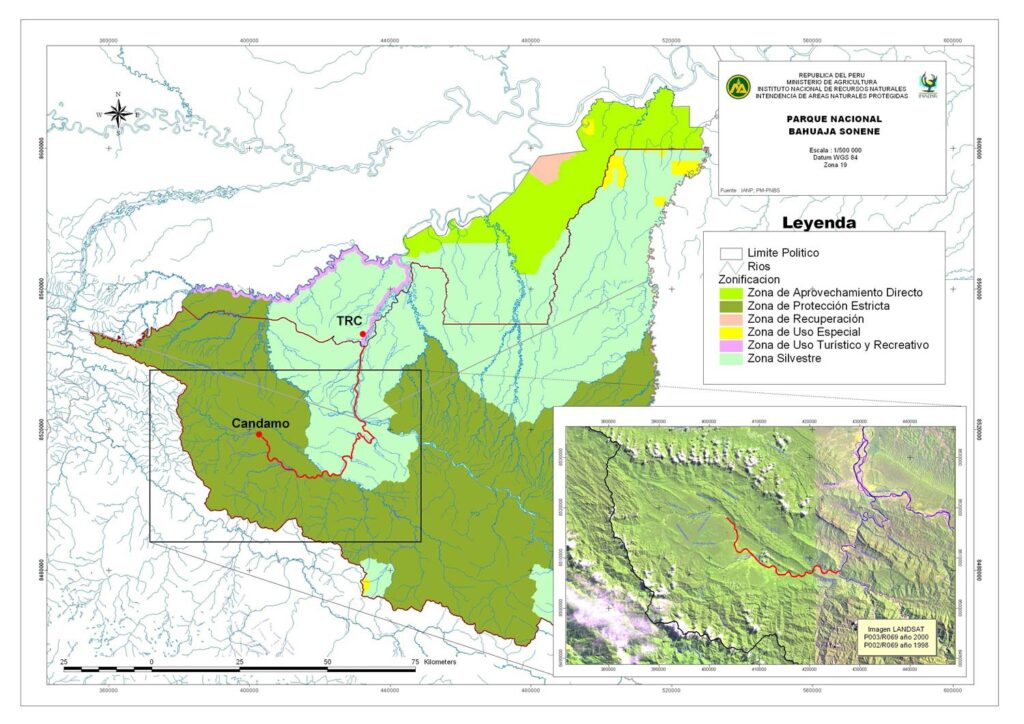

When navigating upstream on the Tambopata River, the foothills of the Andes slowly emerge, covered with lofty rainforest. The river narrows and continues in a rapids-filled canyon, then it expands again. At this point it becomes the Candamo River, named after a 20×30 km (12×19 miles) sized basin nestled among the surrounding mountains. Located in the Puno region, it is a legendary place in the stories of the Ese’Eja people, abounding in fish and where animals are not afraid of people. Their stories may be based on the fact that indigenous tribes have never lived in this basin, perhaps because of its very limited accessibility. In 1996, a Peruvian film – Candamo, La Ultima Selva sin Hombres – depicted the adventurous journey of three members of the Infierno Native Community.

The film was joyful and aimed at praising the beauty of Candamo’s unspoiled nature but also raised awareness about the Mobile oil company’s discovery of a large oil field in the basin. As this area was already assigned as national park, the oil company initiated proceedings to remove the entire Candamo Basin from the proposed protection and to begin to extract the oil. This proposal was presented to the Peruvian Congress, but under international pressure, was rejected. The Peruvian documentary played an important role in this by raising international awareness about the situation. Thanks to this, the Candamo Basin is still part of the Bahuaja Sonene National Park today.

More than two decades later, in 2018, with the support of the Hungarian Media Council’s Patronage Program, we made a second documentary entitled The Macaw Kingdom, in collaboration with the Budapest based Filmjungle Society and Filmjungle Studio. Two of our filmmaker colleagues (Attila Dávid Molnár and Balázs Tisza) accompanied us to one of our research expeditions to the Candamo Basin. Other members of the expedition included ecologist Professor Robert Heinsohn from Australia, science writer Nadia Drake from the USA, Cintia Garai, and three Peruvian crew members (Braulio Poje, Edinson Chavez, and Jerico Soliz). In this 2-week trip we ventured deeper into the basin than ever before.

One of the biggest challenges of the shoot was the lack of electricity and how to recharge the filming equipment. We installed solar panels on the roof of our motorised canoe and used car batteries to store the solar energy. But even so, we were very limited in when and how much we could film. One night, however, it was clear that we had to record an unexpected event with all equipment: a large female jaguar visited our camp next to the river. She mysteriously emerged out of the dark rainforest, and was spotted by film director Attila. Soon, we all gathered with our flashlights and took a closer look (and video) at the big cat standing calmly just a few feet away from us. Given the remoteness of the place, she had probably never seen a human being before. Showing no aggression or fear, but much curiosity, after a few hours she wandered back into the rainforest to resume her secret life. Nothing could have rammed home more clearly just how unspoiled the wildlife is in this ‘Garden of Eden’.

A female jaguar lurking in the darkness at night, in the rainforest of the Candamo Basin, next to our camp site. © Balázs Tisza

Landscape genetics

The strong national protection relieved the Candamo Basin from the threat of oil extraction, at least for now, but there has been almost no research and barely any scientific data to support its biological importance. An important part of my research in the area was therefore to study the genetic diversity of the macaw population living in the Candamo Basin, and its connections to the rest of Amazonia. I have been fortunate to be able to visit this truly special place many times. From the collected samples we created a “genetic map” that took into account not only the physical distance between each sample but also their genetic distance (i.e., relatedness). In collaboration with Prof. Greg Asner from the Global Airborne Observatory and landscape ecologist Dr. Annabel Smith, we overlaid the genetic distance data by different maps produced by remote sensing, including topography, tree height, river system, and the above ground carbon density while controlling for physical distance.

Our results were interesting: the macaw population of the Candamo Basin was genetically different from macaws not very far away in the lowland rainforest of Tambopata. The topography of the area explained the observed genetic distances with the 1,000 m (over 3,000 ft) high mountains surrounding the basin acting as a barrier to the gene flow of these birds even though they can fly long distances (Landscape Ecology 2017 | PDF). The Candamo Basin also hosts a large diversity of other species, some with much more restricted movements than large macaws. For instance, zoologist Zoltán Korsós once joined our research team and he discovered several millipede species previously unknown to science. Based on our results, the somewhat isolated macaw population of Candamo forms a genetically distinct unit. Hence, their protection in the basin is very important for maintaining the full genetic diversity of the species. Landscape genetic analyses thus provided important information for determining the status of the population without capturing the birds, which could not have been done based on observation alone. Researching wildlife using remote sensing and genetic methods may have seemed futuristic in the past, but it may soon be an integral part of current research, monitoring, and management programs.

Receive updates about our films and articles by subscribing to our newsletter: